I invite posts on chess concepts that aren't widely known, if at all known to the chess public yet.

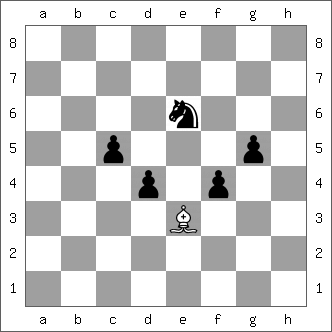

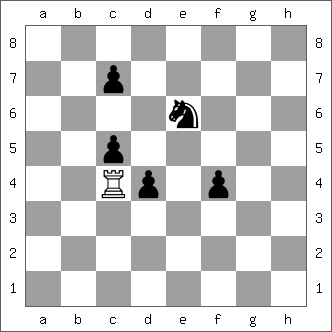

Decades ago, for example, FM Gordon Taylor submitted an article to the En Passant magazine about a concept of his that borrowed a concept from the oriental game of GO. It was about Tsuegi (sp?) against knights. His examples used bishops (and even rooks) achieving an optimal situation against an enemy knight. Two bare bones examples (ignore the Black pawns in each - they are their to show the squares that the White pieces control, in dominating the Black knight to the max):

I can suggest a different sort of concept, which might be seen as remotely related to GM Suba's concept of (waiting for) Information in Chess (also called the Information Game, which often is used by Black in the early part of the game - for example 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2 h6 [or 3...Be7] commits Black as little as possible at move three, he hopes, while waiting to see White's next move/commitment).

My suggested concept, which may need much more fleshing out still (if it is at all useful), is what I call Gatekeeping, especially as it applies to the opening. Either player can be a Gatekeeper at any point in the opening; the aim of a Gatekeeper is to try to get an opening or variation (which is preferably objectively strong) he prefers, hopefully also instead of the one his opponent does. There are three levels of Gatekeeping, based on how strong the openings one limits oneself to with one's chosen move:

Strong Gatekeeping

Temperate Gatekeeping

Tepid Gatekeeping

An example of a strong Gatekeeper is White when Black aims (or maybe even feigns) to get the Marshall Attack in the Ruy Lopez:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0-0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 0-0.

Here White is the Gatekeeper, as he can choose between more than one strong move - 8.c3 allows the Marshall Attack, if White likes facing it, or else 8.a4 (or 8.h3) is an objectively strong alternative, going into an Anti-Marshall.

An example of temperate Gatekeeping is as follows:

1.e4 c5

Here White is a temperate Gatekeeper, as none of his alternatives to 2.Nf3 are objectively strong, but at least one isn't too tepid, namely 2.c3, if he wishes to play it. The c3-Sicilian isn't objectively strong, as far as best chances for winning goes, but if White doesn't mind a draw then this variation can be inconvenient for Black.

An example of tepid Gatekeeping is as follows:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nf6

Here it is already Black who might have been viewed as a strong Gatekeeper, at move three - if White wanted an Evans gambit, for example, Black has chosen an objectively strong alternative that he had available. Now, at move four, White has nothing strong, objectively, other than 4.Ng5 (at least IMO). However White is still a Gatekeeper, albeit a tepid one. He can choose between at least 4.d3 and 4.d4, which are the second best choices here. Neither has [almost] exceptional drawing tendencies, like the c3-Sicilian, at the highest levels - hence White has only tepid choices if 4.Ng5 is not to his taste.

Decades ago, for example, FM Gordon Taylor submitted an article to the En Passant magazine about a concept of his that borrowed a concept from the oriental game of GO. It was about Tsuegi (sp?) against knights. His examples used bishops (and even rooks) achieving an optimal situation against an enemy knight. Two bare bones examples (ignore the Black pawns in each - they are their to show the squares that the White pieces control, in dominating the Black knight to the max):

I can suggest a different sort of concept, which might be seen as remotely related to GM Suba's concept of (waiting for) Information in Chess (also called the Information Game, which often is used by Black in the early part of the game - for example 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2 h6 [or 3...Be7] commits Black as little as possible at move three, he hopes, while waiting to see White's next move/commitment).

My suggested concept, which may need much more fleshing out still (if it is at all useful), is what I call Gatekeeping, especially as it applies to the opening. Either player can be a Gatekeeper at any point in the opening; the aim of a Gatekeeper is to try to get an opening or variation (which is preferably objectively strong) he prefers, hopefully also instead of the one his opponent does. There are three levels of Gatekeeping, based on how strong the openings one limits oneself to with one's chosen move:

Strong Gatekeeping

Temperate Gatekeeping

Tepid Gatekeeping

An example of a strong Gatekeeper is White when Black aims (or maybe even feigns) to get the Marshall Attack in the Ruy Lopez:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0-0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 0-0.

Here White is the Gatekeeper, as he can choose between more than one strong move - 8.c3 allows the Marshall Attack, if White likes facing it, or else 8.a4 (or 8.h3) is an objectively strong alternative, going into an Anti-Marshall.

An example of temperate Gatekeeping is as follows:

1.e4 c5

Here White is a temperate Gatekeeper, as none of his alternatives to 2.Nf3 are objectively strong, but at least one isn't too tepid, namely 2.c3, if he wishes to play it. The c3-Sicilian isn't objectively strong, as far as best chances for winning goes, but if White doesn't mind a draw then this variation can be inconvenient for Black.

An example of tepid Gatekeeping is as follows:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nf6

Here it is already Black who might have been viewed as a strong Gatekeeper, at move three - if White wanted an Evans gambit, for example, Black has chosen an objectively strong alternative that he had available. Now, at move four, White has nothing strong, objectively, other than 4.Ng5 (at least IMO). However White is still a Gatekeeper, albeit a tepid one. He can choose between at least 4.d3 and 4.d4, which are the second best choices here. Neither has [almost] exceptional drawing tendencies, like the c3-Sicilian, at the highest levels - hence White has only tepid choices if 4.Ng5 is not to his taste.

Comment